Sarsaparilla

Angled into the Old Toll Road turnout off Idaho State Highway 21 with snow on the ground and more still falling, our tiny rented Hyundai Elantra gleamed city people. It could only have more thoroughly communicated outsiderness with a lit menorah mounted on the roof. As it was, a sheriff’s deputy from Boise County (not the home of the city of Boise, please note, which sits in Ada County) all-wheeled his truck in front of us with obvious suspicion. R. was in the backseat of the compact attempting to calm down E., who had not only not napped on this drive to Idaho City as we’d been relying on, but had been screaming for miles of winding icy road, requiring R. to nearly disclocate her shoulder while reaching back to hold his soft two-year-old paw as he sobbed, snotted up and fighting the sleep he needed.

I pulled on my surfwear jacket (sometimes I am unconscionably Californian), walked into the snow, and cautiously approached the truck window to talk to the deputy. “I thought maybe you all were sleeping in there,” he said, shifting to show his firearm conspicuously in view. Idaho has been a national leader in criminalizing sleeping outside. You could easily imagine he was eager for the chance to enforce the law of the land, to police bodies gone inappropriately supine under this open Western sky.

So I explained the situation: that we were visiting family and on the road today to go sledding in Idaho City, that my younger son was losing his mind, that my wife was trying to settle him down. Reflexively, I spoke in trad-man patois (“my wife,” possessive, and so on)—as much as possible in cuffed flat-front chinos, anyway—and felt guilty about it. Clear-framed glasses defrosting, oiled-leather Seevees open to the ice. The deputy seemed satisfied enough that we were mostly just hapless, commented that he hoped our car was all-wheel drive (borderline sarcasm, so rare in the West; our feeble vehicle was obviously more than halfway to stuck), then unconvincingly offered help should we need it later. He sped off, splashing slush on our trunk.

E. calmed but didn’t sleep, and we were able to get back to the road without needing to push. We couldn’t, however, figure out how to turn off the Elantra’s automated lane assistance, which guided us against intention, giving the impression the car was skidding on ice even more than it already was. Cede slight control and miss it after in other senses—an intervention mooning an unknown tide. Somehow we made it anyway to Sarsaparilla Ice Cream Parlor, where you can buy tickets for nearby Steamboat Gulch. Then you turn sequentially into deeper woods until you see the hill, wide and white, tamped hard for sledding, left soft enough to crash and laugh about it. A. took immediately to the contained danger of downhill momentum. “World is suddener than we fancy it,” the Irish poet Louis MacNeice once wrote in a poem about snow. Everything screams over the hush of a dampened earth, unbounded by other sound.

“How nearly the state of grace resembled the state of Idaho,” is the thought Marilynn Robinson imagines the grandmother of Housekeeping having at her moment of passing into an afterlife. This is in the would-be town of Fingerbone, presumably based on Robinson’s birthplace of Sandpoint, which is up in the Idaho panhandle—where I would not feel safe even joking about menorahs—and nowhere near Steamboat Gulch. Yet Idaho has an idea to it, wherever you sit inside. (“While Robinson gets away by the skin of her teeth with comparing the state of Idaho with the state of grace,” writes Colm Tóibín, “she wouldn’t were she to find another state of the union and try the comparison a second time.”) I’ve heard so many people dismiss the state when R. says she’s from there. It’s not a part of the interior often considered by the coasts except for when its four electoral votes go red by dint of majority rule. The land itself is only red in the sunset or when the cheatgrass encourages wildfires, which are no longer sporadic and now happen summer after summer. The alpine lakes I’ve seen, for what it’s worth, tend to a deep blue.

In a later essay, Robinson writes about the surprise that others tend to have that she is from Idaho. She often ends up explaining the place. On one hand: “In the West ‘lonesome’ is a word with strongly positive connotations.” But then there is the pleasure of making life with others: “How beautiful human society seems to me, especially in those attenuated forms so characteristic of the West,” she says, with its “regime of small kindnesses, which together, make the world salubrious, savory, and warm.” No one really knows where the name of the state comes from (dismissed conjectures for Idaho etymology: a steamboat, a nonsense pronouncement, a native princess). It was almost Colorado. The local tribes descend from a people who called themselves Newe—which means, simply, “the people”—and gathered in small family clusters that loosely organized into groups when necessary. In one dialect, the verb nemi means both “to live” and “to travel.”

Everything collides on a human scale. Scoped to the geologic lay tiny piles of iced white on each bristle of a mountain’s evergreen, superimposed over centuries. Drill the earth like it has a cavity, spit carbon like spumous chew, ignite your profits like tinder on a stick. Taste bleeds bland as life dries up. Later the Newe became known as the Shoshone, referring to the grass for their conical huts out on the sagebrush steppe. When you leave Boise, you’re taunted by the suddenness of cell service cutting out as soon as you pass city limits; the Treasure Valley, as it is called, requires your full attention. Up north near Sandpoint, in Coeur d’Alene, the Aryan Nations used to march through town streets, the Patriot Front has grown its numbers, and years before the violent coup of January 6, 2021, Stewart Rhodes of the Oath Keepers found inspiration to violently hate more effectively. Parts of the state—along with pieces of Montana, Wyoming, Oregon, and Washington—are claimed by white nationalists as a political resettling region called the American Redoubt. Down at my mother-in-law’s Boise house, on the first night of Hanukkah, we light candles, and, as I do every year, I pull the tunes I never realize I know out of cold storage and sing them into the space between me and my beloveds. Another night we go to a holiday party so bad I end our attendance by screaming “Jesus Christ, stop it!” at A. in a synagogue parking lot. The moon that night is a waning crescent, nearly back to new.

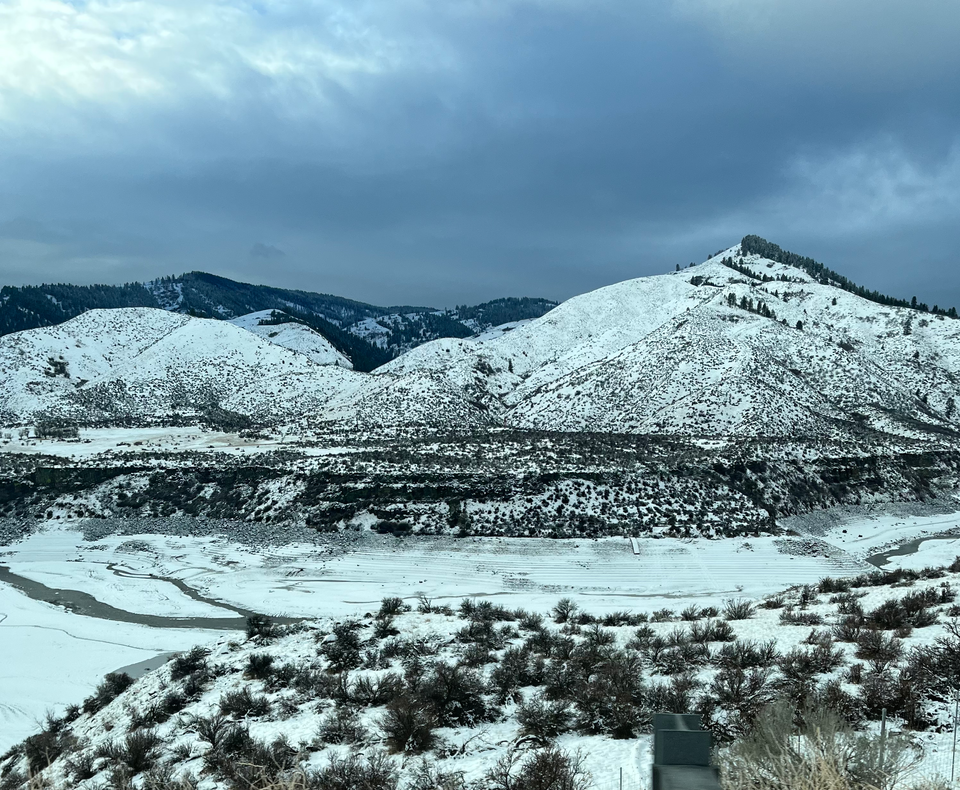

When the kids want to be in snow again a few days later, there still isn’t any in the city. “Why?” A. asks. “I thought it snowed here during winter.” Explaining climate change to a five-year-old without imposing the weight that will fall on his generation’s shoulders is a tender thing. (Though just the other day, Montana youth won a case about their right to have a “clean and healthful environment”—for once, encouraging news of a decent legal decision protecting the world from our human grotesquerie.) We decide to try to find decent sledding closer to Boise and set out for Horseshoe Bend, where it should be cold enough. We roll up Highway 55, alongside the railroad and river. No snow; the children are restless. We go further—still none—and further—nope—and consider turning around. Then it’s sudden: a snap of cover at 4,000 feet. There is nowhere to turn off the road until a place called Smiths Ferry, which seems to consist mostly of a lodge that’s flying a thin blue line flag tangled up and ripped in strips by the wind. We cross a bridge into a small spate of homes with suitable drifts. A camo ATV passes by as I take A. out of the car to put on his gear, and the goateed driver waves.

All around us is private property that we fear to violate. All we want to do is fall down softly among the trees. All we need is gravity and our cheap plastic toboggan. This little patch of forest would be ideal, but R. feels safest playing on the public road, and I believe her. We end up careening down a half-plowed driveway in front of an empty house. I’m recalling how, before he made an ism, Marx wrote about laws that kept the poor from collecting fallen wood—“alms of nature”—from landowners’ property. Who owns the ground, and who gets what hits it? You may neither sleep on public land nor play on private property. How much this patch of earth must laugh at our imagined maps. Does the white pine blanche in doubt of verdant money? The fire loves you, the flame loves you not.

Dark is coming, and we’re due for dinner, so we load the kids up to head back. Years ago R. and I went camping and returned via this same highway through the Boise Forest but neglected to get gas, speeding on empty in neutral, hoping gravity could coast us to a faraway station. Swaths of forest had burned in a recent fire; brush had been cleared to prevent a return. Now we have the kids, who are calm in the back so long as we play “Milele,” from the soundtrack of Mufasa, the latest installation in the Lion King franchise. It’s about searching for a promised land with high grass and blue sky. It has a gentle palpitation to it, the rolling kind of grace you might expect from a song for children about uncertain generational longing. It gets mantric on repeat. Milele is really Pride Rock, which is destroyed by resource extraction and consumed by fire at the end of the original movie. The road dives around as we reenter the snowless zone southward. A partially rotted board displays the Grateful Dead lightning skull painted in faded blue and red. A spray-painted sign on the side of barn declares WE PAWN GUNS alongside a “Take America Back” Trump flag. An empty field bears a beaten marker announcing the future site of the Horseshoe Bend Historical Society. Recently relocated Californians have built hilltop homes with ostentatious roofs as stakes to their claim of this planet. Mine has at least two meanings. The sky breaks purple.

We pack up New Year’s Eve, the night before our flight home, reboxing A.’s new solar system puzzle, with its planets (per his parlance) “Mercuary” and “Unerus.” The kids stuff clothes into their “soupcases.” R. and I. each fall asleep next to one of our children long before midnight. At the end of a year, every statement becomes such a valedictory. Most of what I’ve known is happy accident wishing it had the wisdom of purpose. “The New Year comes with bombs,” wrote MacNeice in another poem, from 1938. He never knew a Cybertruck. Today flames are still consuming Los Angeles, winds piercing everything at 100 miles an hour. Who owns the fire that burns down my friend’s house? Who will own the flood that will drown my city? One moment criminalizes living in the next. This land and that land falsify in translation like from and to do in one language meeting another. Cross a preposition toward my border, please. Every year I feel how much our world is a letter wanting to be spelled in place: the e out of judgment, the i from ordnance, the extra r I didn’t know you needed to make sarsaparilla.