Perfect

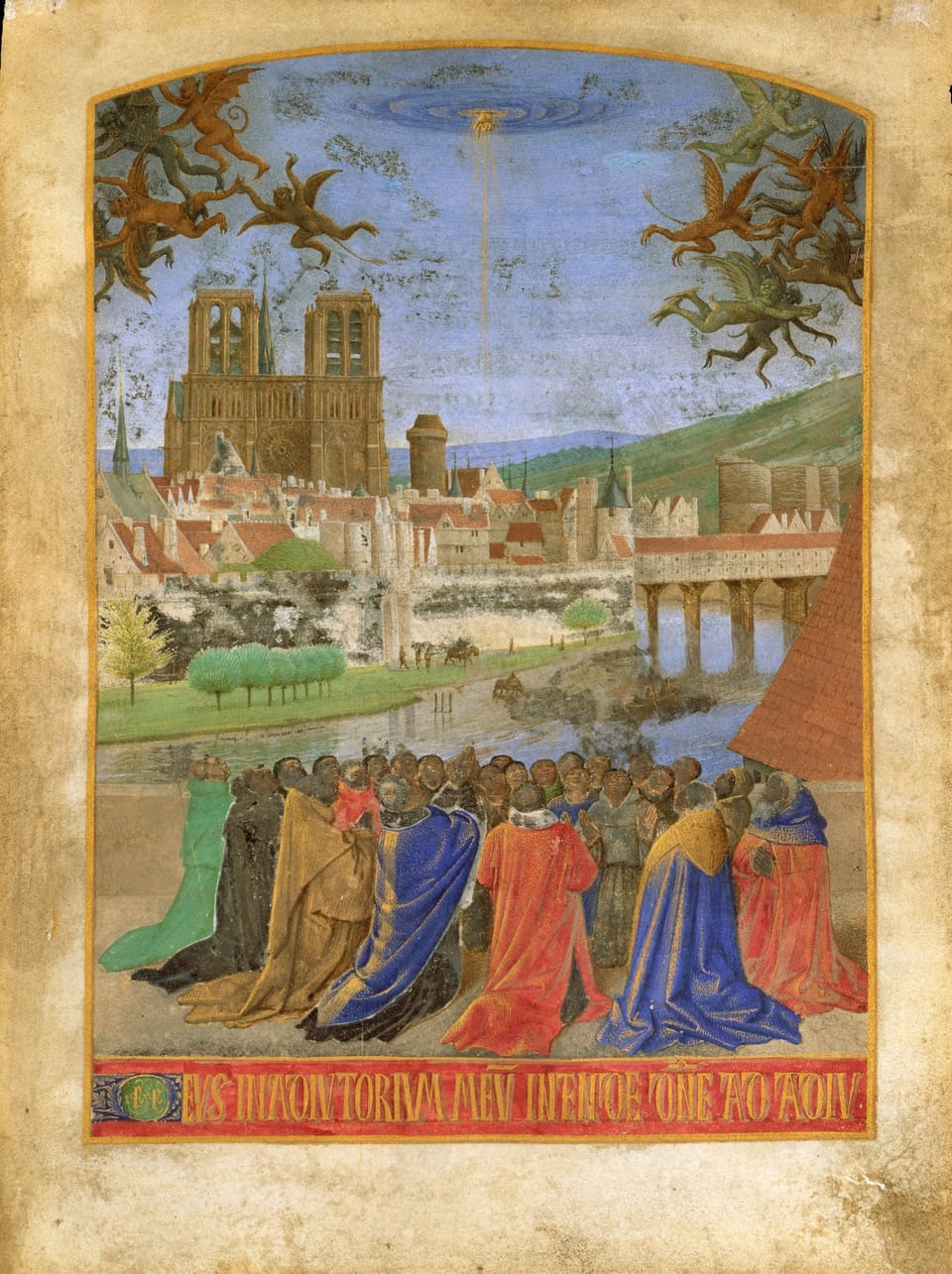

A few weeks before I and a pregnant R. visited Paris in 2019, a fire destroyed the Notre-Dame Cathedral. While avoiding other news today, I read that three of its bells have rung together again. “It’s not perfect yet,” says Alexandre Gougeon, the engineer in charge of the restoration, “but we will make it perfect.” You might be forgiven for presuming, as I did upon reading this news, that these bells are all irreplaceable, centuries old. That hearing them would transport you back to the 4th arrondissement of Victor Hugo, where and when he holed himself up inside his study to write his Hunchback, working entirely naked so as not to be able to leave his maison and miss a lucrative deadline.

But the bells turn out to be pretty new. They were installed only six years before the fire, in 2013. A year before I met R., but nothing that would have awoken Cosette. The new bells replaced temporary sound recordings, which had replaced the previous set of bells, which had fallen so out of tune that local campanologues complained they were unfixable. “This is one of the most dreadful sets of bells in France,” one of them said. (There are lots of sets of bells in France, I’d think.)

These were not the original ones, anyway. The earlier set of bells had largely been melted down during the Revolution to be used as cannon fodder. These dreadful ones were gifted in 1856 by Napoleon III on the occasion of the baptism of his son, Louis-Napoléon. Twenty-three years later, Napoleon IV, as he was by then known, failed to escape local warriors in Zululand, who stabbed him eight times before death and ten times after. A British army surgeon found him stripped naked the next day, save for his medals, which had been left by the Zulus out of respect for the fighter they had defeated. Today’s would-be Napoleon VII is an investment banker with a Harvard MBA who can be found on LinkedIn.

That set of bells melted during the Revolution weren’t the originals either. They replaced ones that weren’t the originals, which weren’t the originals, and so on. We know about the first bell of Notre-Dame because Bishop Eudes de Sully, who inherited the project of the cathedral’s original construction and is also known for trying to ban priests from playing the vain game of chess, mentioned it passingly in 1198. He was more interested, though, in a polyphonous style of music, new in his time, called ars antiqua. From that ars we get the motet, a sacred choral form named for the French word for word. The last time I was in anything close to a medieval cathedral was when I heard Janet Cardiff’s Forty-Part Motet in the Met Cloisters, which sent my mind fetal in layman’s worship. A deliberateness painted with forever echo.

Most of what I remember about seeing Notre-Dame six years ago is simply not really seeing Notre-Dame. I heard later, a few years after we went, that an artist got permission to put an accelerometer inside the oldest surviving bell, a bourdon cast in 1686 named Emmanuel, which was the one lucky bell to have escaped melting multiple times. Emmanuel was silent in 2022, as cathedral reconstruction was still under way. Although: not silent, apparently. The artist measured the low vibrations it emitted in response to its environment, which is to say the sound it made when rung by the world and not by a clapper. He adjusted the recordings to levels a human could apprehend. Doing this was a tough sell to the Paris authorities. “A game of chess,” he called it.

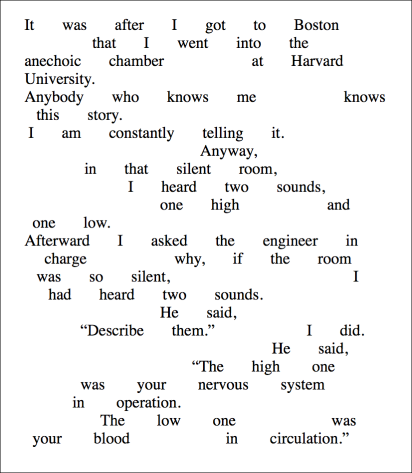

Inside an unrung bell is an audile womb you feel before hearing. Most of what we know is mostly unknown to us. John Cage visited the anechoic chamber at Harvard and left confused, then formed a life philosophy out of it. The story Cage perfected and recorded for Indeterminacy was: He asked the engineer why a place meant to be perfectly silent left him hearing two sounds, one high and one low. “The high one was your nervous system in operation. The low one was your blood in circulation,” the engineer said. It’s possible, say some physicians, that what Cage heard was just plaque building in his arteries on their way to the stroke that killed him at 79. Though I don’t know how it matters, really, whether it was death or life ringing his bell, a good or bad vibration heard for a moment in time.

I’m glad there are bells at Notre-Dame that rang in a familiar way and can ring on schedule again, but I’m not certain what further perfection an engineer is imagining he can bring. Noisy silence, a broken peal, a naked rush, what’s left after death to be recast into other forms. A perfect bell would seem to belong somewhere else, don’t you think? In a different cathedral, for an alien physics. There are forty separate speakers singing melded melodies to you when you submit to Cardiff’s motet. They surround you inside their body, and you become a small thought of life carried around the world before birth. All of the voices are perfectly broken; all of them are perfectly whole.