Harmony

The spacing of things, which change from screen to screen. You have to know to look to shift them. You need a particular gift for pixels in balance. “No embellishment please, the day / is sufficient” is a line the poet Peter Gizzi published once. I’m considering windowpanes and the tensile strength of a paragraph.

As a young kid (or maybe still) I was not very good at performing opinions. A favorite color or a sense of future profession: these are presumptive childhood questions for which there really should be easy responses. To own an answer you need to handle self-knowledge with embryonic care. “Do I have the right to be? Is being in the world not taking the place of someone?” These are questions the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas once asked. He also said, “In principle the I does not pull itself out of its ‘first person’; it supports the world.” This I like to think. “My responsibility is untransferable, no one could replace me.” This I want to believe.

I lacked a natural sense of what I was meant to enjoy or want to be, or didn’t know how to hear it, or didn’t know how to perform it. Whatever the case, I became very good at interpreting a present field of options to hone in on its model of desire. My older brother, S., bore most of this burden—supplying the architecture of wanting I tried to hide within—but so did adults, less one specific adult than the mechanism of adulthood. I presumed their age had brought worldly expertise. I often guessed wrong, faltering when an answer I had isolated as correct was unloved by another. Mostly I carried others’ cares from place to place, a mule porting food and water across a weedy field. I suspect, like most people trying to copy another, I revealed myself in my missenses; I misapplied as strange mutations. I hid from inclinations. “Those who feel want to,” is something my old friend J.L. wrote in a brilliant poem. I’ve tried.

Reading can be a way to find yourself, and it can be a way to hide yourself. From time to time I’ve wondered: Am I rescuing my thoughts from myself through language, or is language rescuing myself from my thoughts? Often I’m not legible; often the world isn’t. There’s a grammar to the balance of being in this orbital. I want to redo all the years of reading to read rather than reading to listen and respond and be. What if I could have considered myself worthy of awe, of anger, of desire, of power, not just of playing chase with a fuzzy subject? I might followed my sensitivities through their aberrant paths, far past the consummate wrongness of things to you. There’s a reason we call movement leaders organizers, even though they have to disturb us first. We might have made an earth. The smell of the books was good, in any case, in a twin bed, flipping pages past my face. Slowly, over time, writing started to warm and hurt like music could, and I realized that this is what people whose taste was baked in love could feel all the time. You have to be someone who can give of yourself to really get anything from a book. At some point I stumbled into college. There I recall another friend, L.F., wiser and more self-possessed than me, telling me I should stop marking up books in pencil and start using pen. “It seems like you’re afraid of being permanent in your own books, and you should stop that,” is what she said.

I’m getting somewhere with this. “The world interdepended with me—that was the confidence I had reached: the world interdepended with me, and I am not understanding what I say, never! never again shall I understand what I say,” is something Clarice Lispector wrote in the character of G.H., and I think I understand her. Over time, I’ve come to recognize how becoming blooms belonging, and back again. It might take a base act, speaking over a cliff. If you’re fortunate, as I have been, you could discover the way a sensibility merges with others’ and deepens a channel through the world. I found my way under the brow (arched and/or furrowed) of Lewis Lapham—not, at first, him as a person, but the wake he left among young Americans who needed to bend ideas seriously while also knowing joy. Bobbing about in that kindred wake is how I found R. and trusted our love. Later, I met Lewis himself and finally started learning how to mark up the world’s margins in ink. Through him I came to understand the art of the checkmark reaction, the nodding along, and someday I’ll have to try to chart that half-decade of life. I’ll also have to reckon with how the checkmark can be grotesque, stops at the page’s edge, and doesn’t fully consider the river.

Still none of this is why I started writing this down. This past weekend I went to the re-opening of the wonderful East Bay Booksellers, whose storefront had burned down in a fire some months ago. I brought A., who bolted for the picture books and found a tale about dragons and tacos. There’s so much to love about this shop, but the reason that stood out, standing there in the yawn of an afternoon, was a genuine pleasure of realizing you are in exchange with it, ballooned by it, in motion inside it. It is not often enough we get the feeling of occupying a physical space—body leaning toward middle age, gut fizzing, head spun in horror and need, wanting to act out some desperate swoon of justice—and get to grasp the true potential of a shared sensibility. Only a consumer in a technical sense. In that shop, there is an opinion about the world and what it should be. The wood shelves are fresh, and the paper is fresh, and the ink is stained into what ways we humans might care—for one another, for you along with me and them as us, with the kind of responsibility for we only an I, reader can atomically combine. The bestselling book of this store (because its owner, Brad, recommended it widely) is Power of Gentleness by the philosopher Anne Dufourmantelle, who died in 2017 while saving two children from drowning off the coast of Saint Tropez. “Gentleness is what allows us to reach out to this stranger who comes to us, in us,” is one of the many indelible lines from this book, which is more than sufficient.

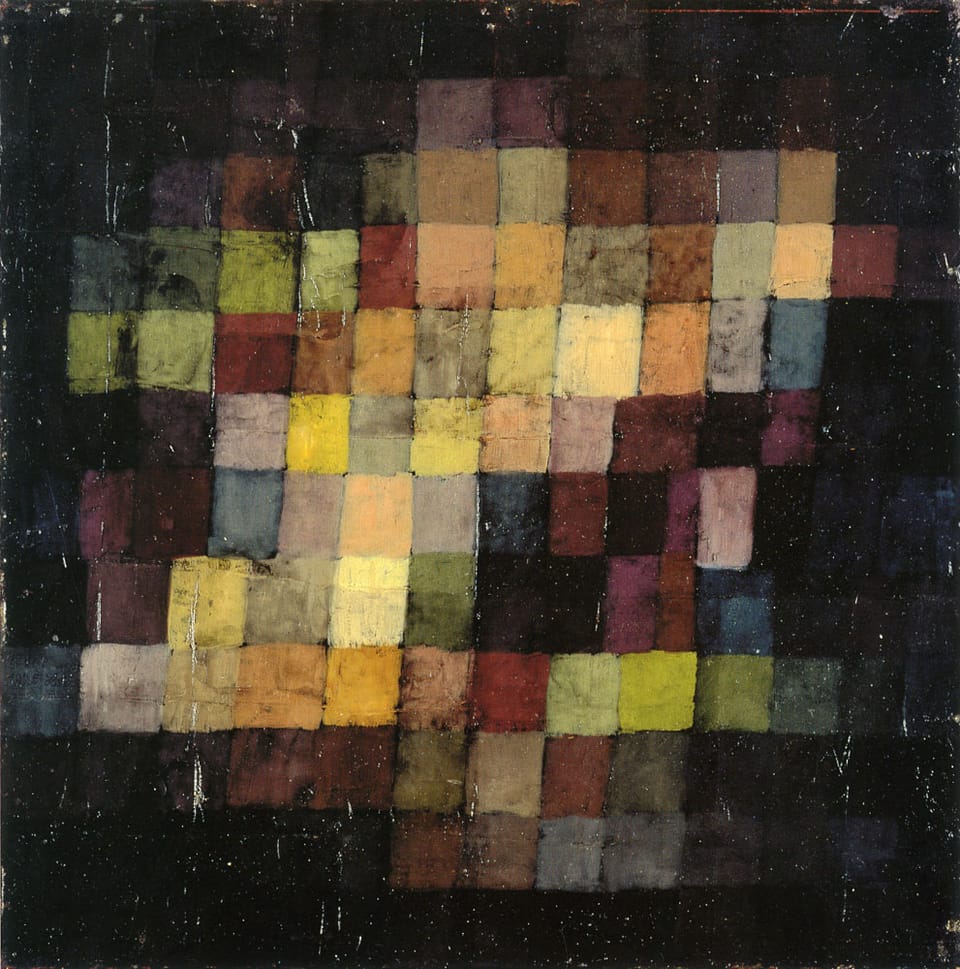

I’ve been feeling in need of a sense-making space. The past few years—and acutely the past month—I’ve had an urge to fight away from my life as a creature of screens, quietly nodding along. To be drawn locally and draw others in turn. It’s simply not common enough to get to stand in a room with other people who hope and dream and critique and want to build the way you hope and dream and critique and want to build, with specific books—not a general, anodyne category of book-thingness, but books that deserve to exist—standing in witness. It’s not itself a movement, but it’s a shifting into shape. All good things begin when you hit this harmonic. What happens after matters.

Beloved theorist Lauren Berlant once wrote about optimism that “at any moment it might feel like anything, including nothing.” Will the sought-for future be cruelly withheld or somehow achieved? I have only an opinion—though, it turns out, closely held. Finally I get the point, that I’m pointing one way and not the other, not forcing adornment, resonant in real space.